PASADENA, Calif. – The 33-year odyssey of NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft has reached a distant point at the edge of our solar system where there is no outward motion of solar wind.

Now hurtling toward interstellar space some 17.4 billion kilometers (10.8 billion miles) from the sun, Voyager 1 has crossed into an area where the velocity of the hot ionized gas, or plasma, emanating directly outward from the sun has slowed to zero. Scientists suspect the solar wind has been turned sideways by the pressure from the interstellar wind in the region between stars.

The event is a major milestone in Voyager 1's passage through the heliosheath, the turbulent outer shell of the sun's sphere of influence, and the spacecraft's upcoming departure from our solar system.

"The solar wind has turned the corner," said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist based at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif. "Voyager 1 is getting close to interstellar space."

Our sun gives off a stream of charged particles that form a bubble known as the heliosphere around our solar system. The solar wind travels at supersonic speed until it crosses a shockwave called the termination shock. At this point, the solar wind dramatically slows down and heats up in the heliosheath.

Launched on Sept. 5, 1977, Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock in December 2004 into the heliosheath. Scientists have used data from Voyager 1's Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument to deduce the solar wind's velocity. When the speed of the charged particles hitting the outward face of Voyager 1 matched the spacecraft's speed, researchers knew that the net outward speed of the solar wind was zero.

This occurred in June, when Voyager 1 was about 17 billion kilometers (10.6 billion miles) from the sun.

Because the velocities can fluctuate, scientists watched four more monthly readings before they were convinced the solar wind's outward speed actually had slowed to zero. Analysis of the data shows the velocity of the solar wind has steadily slowed at a rate of about 20 kilometers per second each year (45,000 mph each year) since August 2007, when the solar wind was speeding outward at about 60 kilometers per second (130,000 mph). The outward speed has remained at zero since June.

The results were presented today at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

"When I realized that we were getting solid zeroes, I was amazed," said Rob Decker, a Voyager Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument co-investigator and senior staff scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. "Here was Voyager, a spacecraft that has been a workhorse for 33 years, showing us something completely new again."

Scientists believe Voyager 1 has not crossed the heliosheath into interstellar space. Crossing into interstellar space would mean a sudden drop in the density of hot particles and an increase in the density of cold particles. Scientists are putting the data into their models of the heliosphere's structure and should be able to better estimate when Voyager 1 will reach interstellar space. Researchers currently estimate Voyager 1 will cross that frontier in about four years.

"In science, there is nothing like a reality check to shake things up, and Voyager 1 provided that with hard facts," said Tom Krimigis, principal investigator on the Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument, who is based at the Applied Physics Laboratory and the Academy of Athens, Greece. "Once again, we face the predicament of redoing our models."

A sister spacecraft, Voyager 2, was launched in Aug. 20, 1977 and has reached a position 14.2 billion kilometers (8.8 billion miles) from the sun. Both spacecraft have been traveling along different trajectories and at different speeds. Voyager 1 is traveling faster, at a speed of about 17 kilometers per second (38,000 mph), compared to Voyager 2's velocity of 15 kilometers per second (35,000 mph). In the next few years, scientists expect Voyager 2 to encounter the same kind of phenomenon as Voyager 1.

The Voyagers were built by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which continues to operate both spacecraft.

JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena

Português. (by ASTRONOMIA ON LINE)

A odisseia de 33 anos da sonda Voyager 1 da NASA alcançou um ponto distante da fronteira do nosso Sistema Solar, onde não existe movimento externo do vento solar.

Agora viajando na direcção do espaço interestelar a uns 17,4 mil milhões de quilómetros do Sol, a Voyager 1 alcançou uma área onde a velocidade do gás quente ionizado, ou plasma, que emana para fora do Sol, diminuiu para zero. Os cientistas suspeitam que o vento solar está agora "de lado" devido à pressão do vento interestelar na região entre as estrelas.

O evento é um grande marco na passagem da Voyager 1 pela concha turbulenta da esfera de influência do Sol e da sua futura despedida do nosso Sistema Solar.

"O vento solar 'virou a esquina'", afirma Ed Stone, cientista do projecto Voyager no Instituto de Tecnologia da Califórnia em Pasadena, EUA. "A Voyager 1 aproxima-se do espaço interestelar."

O nosso Sol liberta uma corrente de partículas carregadas que formam uma bolha conhecida como heliosfera em torno do Sistema Solar. O vento solar viaja a velocidades supersónicas até que atravessa uma onda de choque denominada choque de terminação. Neste ponto, o vento solar diminui dramaticamente de velocidade e aquece.

|

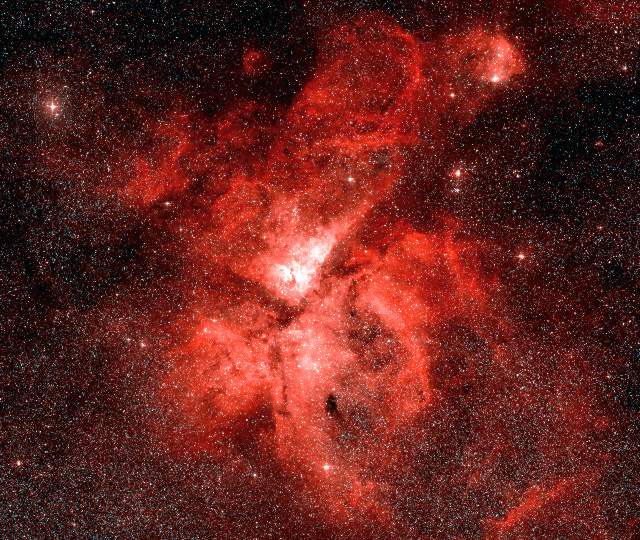

Ilustração de artista da sonda Voyager 1.

Crédito: NASA/JPL |

|

Lançada a 5 de Setembro de 1977, a Voyager 1 atravessou o choque de terminação em Dezembro de 2004. Os cientistas usaram os dados do LECPI (Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument) para deduzir a velocidade do vento solar.

Quando a velocidade das partículas carregadas que atingem o lado da sonda contrário ao do Sol coincidiram com a sua velocidade, os pesquisadores souberam que a velocidade do vento solar era zero. Isto ocorreu em Junho, quando a Voyager 1 estava a 17 mil milhões de quilómetros do Sol.

Dado que as velocidades podem flutuar, os cientistas registaram mais quatro leituras mensais antes de se convencerem que a velocidade do vento solar tinha realmente diminuído para zero. A análise dos dados mostra que a velocidade de vento solar diminuiu firmemente a cerca de 72.420,48 km/h por ano desde Agosto de 2007, quando o vento solar viajava a cerca de 209.214,72 km/h. A velocidade permanece nula desde Junho.

"Quando me apercebi que estávamos a receber zeros sólidos, fiquei impressionado," afirma Rob Decker, co-investigador do LECPI da Voyager e cientista do Laboratório de Física Aplicada da Universidade Johns Hopkins em Laurel, Maryland, EUA. "Aqui estava a Voyager, uma sonda que trabalha arduamente há já 33 anos, mostrando-nos outra vez algo completamente novo."

Os cientistas acreditam que a Voyager 1 ainda não entrou no espaço interestelar. Isso significaria uma súbita descida na densidade de partículas quentes e um aumento na densidade de partículas frias. Os cientistas estão a colocar os dados nos seus modelos da estrutura da heliosfera e deverão ser capazes de melhor estimar o momento em que a Voyager 1 irá atravessar para o espaço interestelar. Actualmente estimam que chegará a essa fronteira daqui a quatro anos.

"Em Ciência, não há nada como uma verificação da realidade para agitar as coisas, e a Voyager 1 ofereceu-nos uma com factos concretos," afirma Tom Krimigis, investigador principal do LECPI, do Laboratório de Física Aplicada e da Academia de Atenas, Grécia. "Uma vez mais, enfrentamos o desafio de refazer os nossos modelos."

Uma sonda-gémea, a Voyager 2, foi lançada a 20 de Agosto de 1977 e está a 14 milhões de quilómetros do Sol. Ambas as sondas viajam a trajectórias diferentes e a velocidades diferentes. A Voyager 1 viaja mais depressa, a uma velocidade aproximada de 61.155 km/h, em comparação com os 56.327 km/h da Voyager 2. Nos próximos anos, os cientistas esperam que a Voyager 2 encontre o mesmo tipo de fenómeno que a Voyager 1.